|

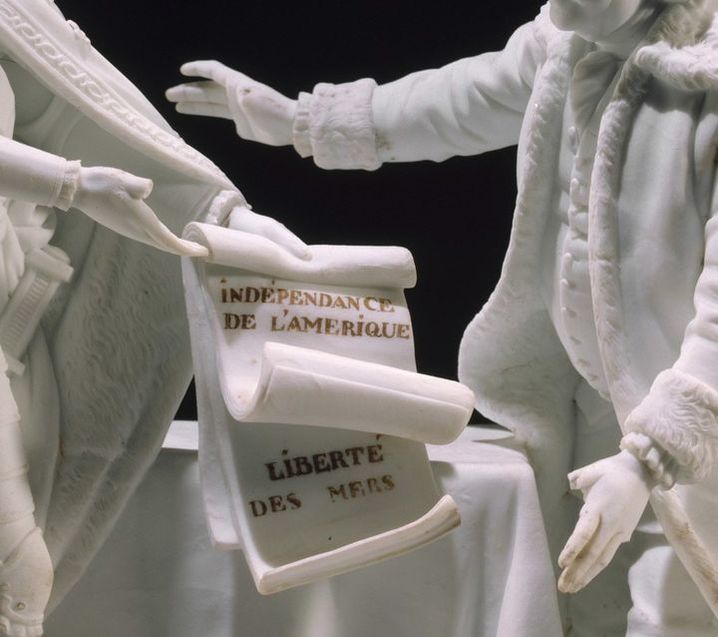

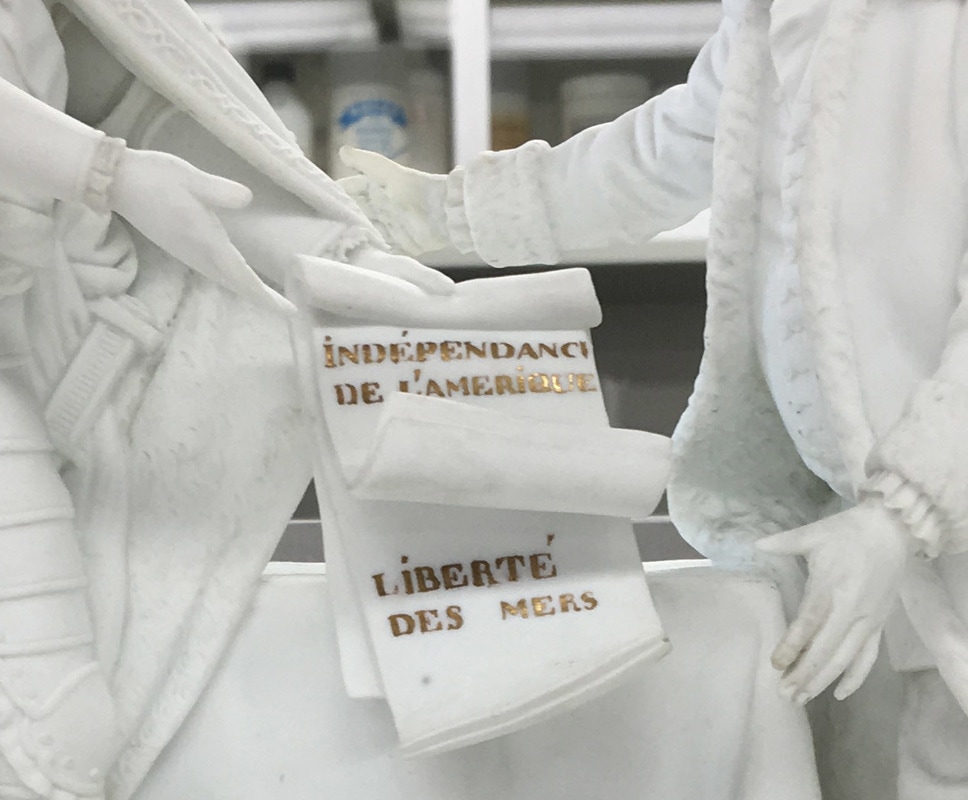

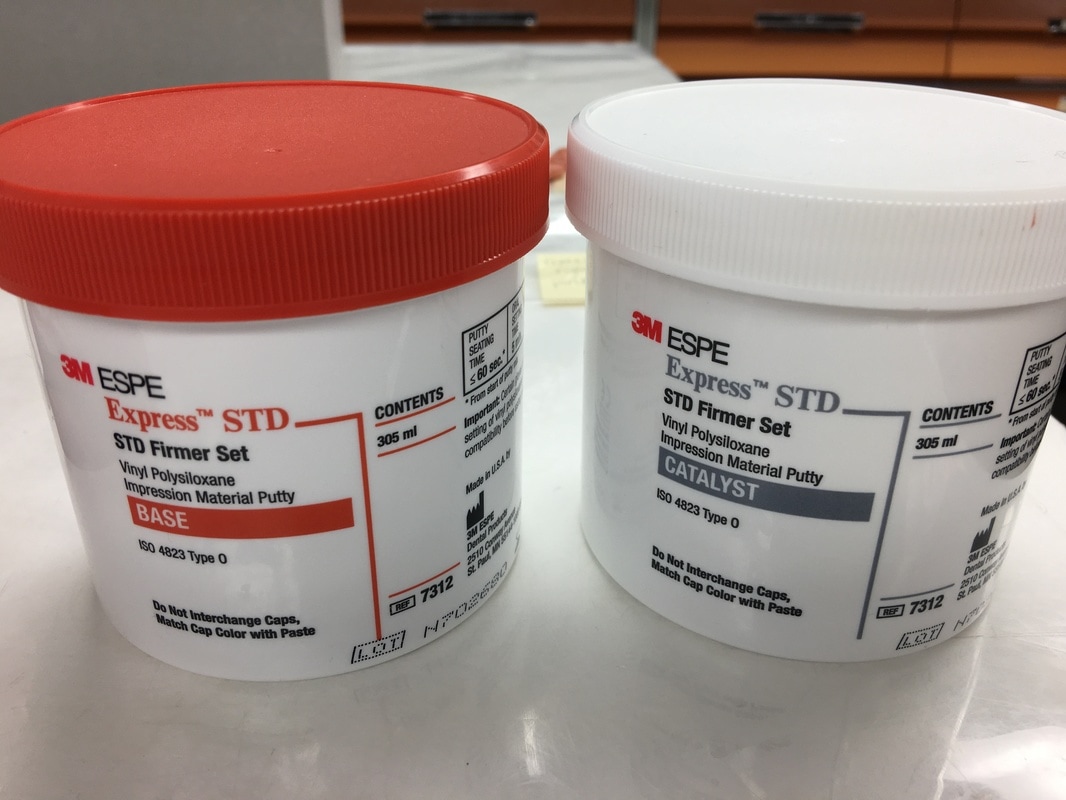

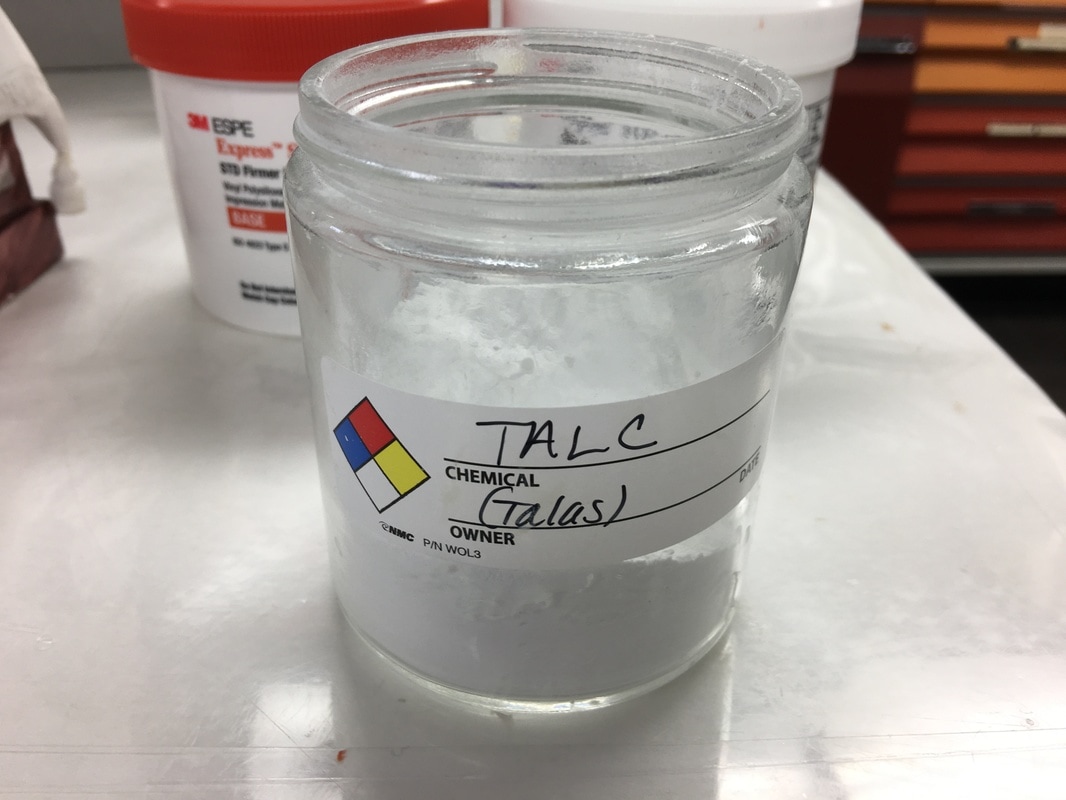

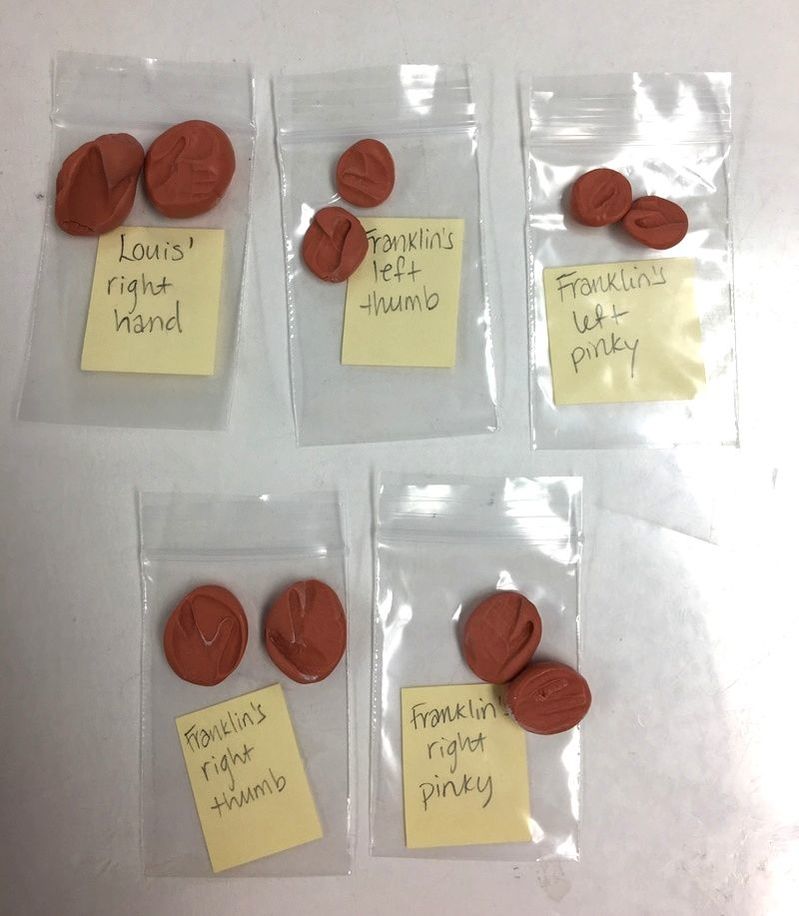

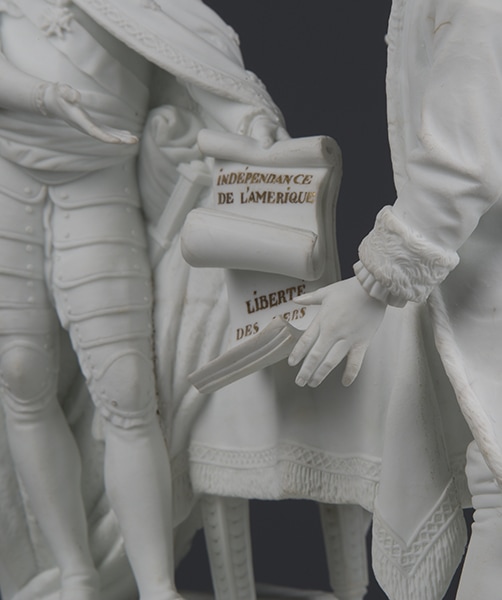

Okay, Lauren, what in the heck is this blog post about? Basically, it's an example of when your day as a conservator can bring the unexpected. I recently got a phone call from my former supervisor, the ceramics conservator extraordinaire, Wendy Walker, who works at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They have a sculpture by the French artist, Charles-Gabriel Sauvage, depicting Louis XVI and Benjamin Franklin commemorating the moment in 1778 that France and the United States signed two treaties between their countries. Wendy has been tasked with treating this sculpture, as it is in need of cleaning, and several fingers are missing from both Louis and Benjamin. Hand-modeling tiny fingers to look like bisque porcelain would be a difficult task for anyone. And although Wendy is one of the most talented ceramics conservators I know, her work would go much better if she had access to extant fingers from which to take molds. Luckily, Winterthur has a nearly identical sculpture by Sauvage, and – you guessed it – our fingers are intact! Happy to help, Wendy and I strategized over the phone at the approach I would take. We decided I would use a two-part siloxane putty for each figure hand in need of a mold, and then I would drop these in the mail. Because bisque porcelain is not glazed, it has a measure of porosity to the body that makes it susceptible to absorbing anything applied to it, such components of a silicone or siloxane mold. To limit absorption, I first dusted the figure hands with talcum powder before applying them. After prepping the surface, I could then proceed, making two-part molds for each hand, or thumb, or pinky. An update: Benji Franklin has his fingers back4/23/2017 Wendy completed her treatment of the Sauvage sculpture, utilizing the molds from the Winterthur mate. She shared her detail documentation photos after treatment, and you can see that Benji's hands once again have all ten fingers. Awesome work! Another update: Louis and Benji become Poster Children5/6/2018 A show opened in April 2018 at the MET called Visitors to Versailles (1682-1789), and the newly-conserved Sauvage sculpture was made the poster child for the show. If you find yourself in New York, check it out - the show is up through July 29, 2018.

3 Comments

Take the example of the outdoor public work entitled Always Becoming, a sculpture by artist Nora Naranjo-Morse of Santa Clara Pueblo for the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). You can read the article here, published by Naranjo-Morse and two NMAI staff, conservator Kelly McHugh and collections manager Gail Joyce. If you want to know more, watch the 30-minute video on the project below. In this case, the artist's intent for her work, a family of five clay structures named Mother, Father, Little One, Moon Woman, and Mountain Bird, would take on a life of their own, allowing the natural elements outside the NMAI on Washington's National Mall to affect and change their forms over time. This would include, of course, a gradual decay or movement back into the earth, a concept of the life cycle very central to Santa Clara Pueblo oral tradition. In many ways, this project had all the elements in place to make it hugely successful from the perspective of all parties involved. First, the NMAI knew Naranjo-Morse's intention for the piece before they accepted it into their outside exhibit space; therefore, they could be sure they had all the resources needed to ensure that her wishes would be met. From the museum's standpoint, this included regular documentation of the sculptures to record their change with time, as well as regular communication with the artist to discuss what change was acceptable and what change should be addressed. Second, the agreement was for Narajo-Morse to return every year to oversee any maintenance that should take place, or more commonly, what "assistance in the decay" needed to occur to keep the sculpture's integrity present, while allowing them to continue their natural life cycle. In this way, the conservators and collections managers could take the artist's lead in these kinds of decisions, making it an effective collaboration all the way through. So with Always Becoming there was a well-designed plan in place, and active stewards ready and able to see that plan through. But what about the times that is not possible? Not every institution can take on a project like this; nor should they. And sometimes an artist can just change his or her mind! Take the example that one of the students shared during our discussion: Ilya Kabakov's School No. 6 at the Chinati Foundation. The work occupies an entire building that is subdivided into rooms, recalling an abandoned schoolhouse from the former Soviet Union. When Kabakov installed this work in 1993, he intended for the peeling paint on the walls and the faded photographs and paper writing samples that fill the desks and other spaces to continue to degrade over time, thus adding to the sense of abandonment that is so central to the work. However, when the artist visited the space 20 years later, he was appalled to see the rate of degradation, due to the plethora of natural West Texas sunlight pouring in. Currently, the Chinati conservation staff are working to find ways to halt the degradation processes, which was not initially the plan for this work. This change in intention, while understandable, creates a need for resources that were never originally accounted for, and not every institution can manage the request.

And where does the conservator fall in all this? Do we as conservation professionals have a moral obligation to make interested parties aware of material limitations and degradation processes? For instance, if we know a certain material will within ten years time look dramatically different from the day an art collector is thinking of purchasing it, how does our input affect the value of that work - perceived or otherwise? And how might our input affect artists who work with the materials they have available to them, despite concerns of longevity?

Our group decided that we as conservators do have a responsibility to inform buyers or owners of how best to care for the works that will fall under their stewardship. This includes creating awareness of material limitations or special needs in regards to light levels, environmental parameters, or even limited lengths of display. If given a seat at the table, we can become important neutral parties to help an artwork on its life path beyond artist creation. prefaceIf you want to do great things in life, you have to start by walking in the footsteps of great people. I had the pleasure of working with Chela Metzger for four years of my career and witnessed first hand how her laid-back attitude and genuine passion for book conservation and ethical considerations in the field rubbed off on everyone she talked to. This was especially true with the graduate students. Chela instituted a series of "Philosophy Chats" within the second-year curriculum that enabled students to talk with their professors in a casual, open, and judgement-free zone, on various topics within the field of conservation. When Chela left WUDPAC to become the Head of the Conservation Center at the UCLA Library, another inspiring individual carried on the "Philosophy Chat" torch: Dr. Stephanie Auffret. One of Stephanie's many passions is the examination of authenticity within the decorative arts. In fact, in 2010 she received her PhD in Art History, from the University of Paris IV Sorbonne, entitled The Authenticity of French Furniture: Interpretation, Evaluation and Preservation. Her deeply-rooted research background paired with her friendly and lively personality kept Chela's initiative alive and strong. Last year, Stephanie took a job as Project Specialist at the Getty Conservation Institute, and there was no longer a driving force to lead these philosophical discussions. That is when Melissa Tedone and I stepped in. You see, she and I both love hashing things out. In fact, we are even in a book club together in our time outside of Winterthur, and Melissa studied under Chela in her days of graduate school at the University of Texas at Austin. We felt ready to take on this tradition. philosophy chats 2016-2017This Academic year, Melissa and I put together a series of six topics with associated readings that we would ask the students to read ahead of time to then discuss over a lunchtime session. And I will note, we made none of these sessions mandatory: anyone could choose to participate (or not) as they wished. Our topic line-up:

diversity, equity, and inclusion in conservationSo our first topic did not shy away from tough conversations. For this Philosophy Chat, those who participated read the transcript of the brilliantly courageous talk given by Sanchita Balachandran at the 44th annual meeting of the AIC, held in Montreal, Canada this year. Her talk was entitled, “Race, Diversity, and Politics in Conservation: Our 21st Century Crisis,” and you can read the transcript for yourself here. Sanchita's talk was really one that needed to be given to our field, and though I was not there to hear it in person, I learned that she received a standing ovation after delivery, a rare occurrence at an AIC meeting. The talk discusses the dire need for diversification in our field, and not just so that we can pat ourselves on the back if we have a variety of skin tones sitting at the table. It is about the deeper levels of how we care for the tangible and intangible qualities of cultural heritage and recognizing who we are treating these objects for. A big topic of discussion centered around the recent debate in Baltimore regarding four Confederate monuments and the many complex feelings that they bring out in a community wrought with turmoil over racial imbalances. As conservators, we are taught to treat every piece of history as an "artifact" worthy of preserving. But are these relics standing strong as painful reminders of a difficult past worthy of that today? And who are the people that should be making that call? If you are interested in following the Baltimore discussion, I recommend you start by reading the report by the Special Commission to Review Baltimore's Public Confederate Monuments.

Another discussion came up regarding the often understated problem of the lack of diversity within the conservation profession. There is real data documenting the ethnic breakdown of professionals working in the field of conservation, but I'm pretty sure you can guess what that pie chart looks like. As of 1993 the number was 95.1% White. And my bet would be it hasn't changed all that much in 20 years. A 2015 study conducted by the Mellon Foundation found that White (non-Hispanic) individuals comprise 84% of all the art museum staff associated with the intellectual and educational mission of museums, including curators, conservators, educators, and leadership positions. There is a real discrepancy, and it starts at the level of who even has the privilege to work towards a graduate degree in art conservation, let alone get in. This raises real issues when it comes to who makes up the conservation profession, why we treat objects of cultural heritage, who has real "ownership" of those objects, and who we are treating them for. There is no answer that can be typed out in black and white. There are a million shades of gray, and it will take many voices standing up and speaking out and making change happen. "Our work has to support and make possible the right of people to tell, sing and perform their own narratives of their own cultural heritage." I am glad Melissa and I are holding these Philosophy Chats. I am thankful to all the students who attended this session. It was a bit sobering, to be honest, but important to discuss. And now I want to leave you, Blog Reader, with Sanchita's closing statements:

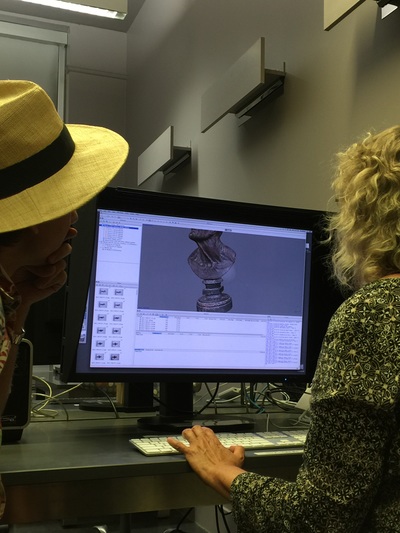

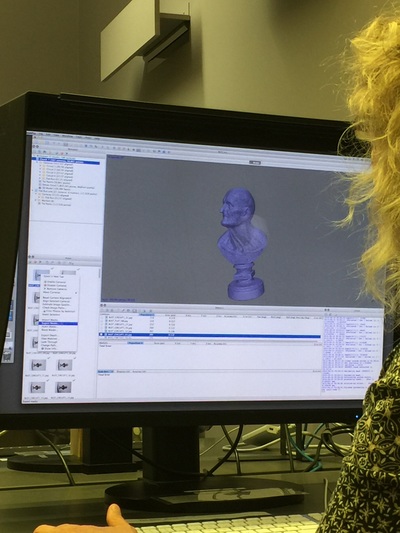

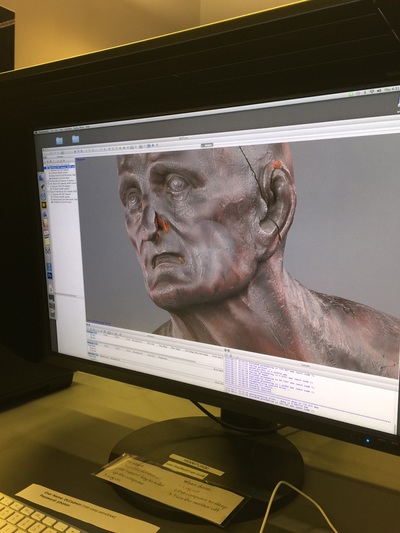

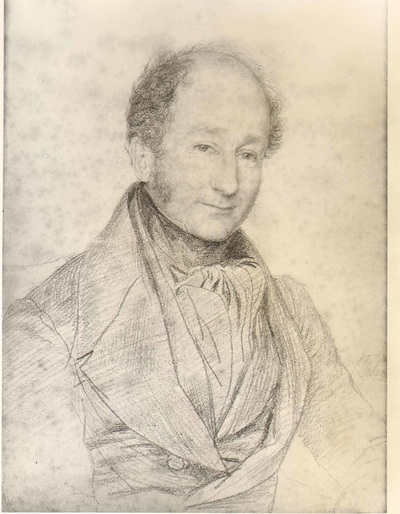

According to its Wikipedia page, photogrammetry is the science of making measurements from photographs, especially for recovering the exact positions from surface points. By sticking to a well designed protocol for image capture, as well as tested and proven methods for optimizing photo processing, one can create highly precise and measurable 3D models. Compared to laser scanning, this is as good, if not better, due to its superior metrics and archiving options. And in our world (of conservation), precise rendering in documentation practice paired with long-term preservation is everything. CHI has a great explanation of photogrammetry on their site, which explains the technique much better than I can here. This technique can be used on sites like archaeological digs or on individual artifacts for high level rendering and photodocumentation; for instance, a dig site can be documented prior to reburial. It can also be used for public outreach and to enhance visitor experience, such as to create a 3D experience of a site or place the public may not be able to enter. It can be used to print accurate 3D models that can be used in conservation practice for loss compensation or custom mount-making, or for important research such as investigating how an object was made or what has happened to it since manufacture. Really, there are many possibilities, and as the technique develops further and more conservators use and refine it, we will continue to discover new applications. I share with you a short video of the 3D model we made of the Roman senator bust at Buffalo, so you can get the idea of a "quick and dirty" output. This is literally a video shot with my iPhone of my computer screen as I manipulated a 3D pdf. So don't judge the quality!

So for my very first blog post I have decided to tell you how Winterthur got its start, and for that we have to go back to the year 1801, and yes... to gunpowder and sheep. Eleuthère Irénée du Pont (Irénée) was not only founder of the gunpowder manufacturing firm E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company and patriarch of what would become one of the most rich and powerful families in Delaware, but he was also a lover of Merino sheep! In 1801, shortly after arriving in the United States with his family, Irénée had a purebred Merino ram, venerably named Don Pedro, brought over from France. A fun sidebar story that Jeff Groff, our Estate Historian, told me is that among the group of rams brought over to America (of which only Don Pedro survived), some were bound for Thomas Jefferson’s home at Monticello. Did you know that Jefferson was an avid ovine enthusiast??? In fact, upon Don Pedro's death in 1811, Thomas Jefferson himself sent a letter of condolence to the du Ponts. Don Pedro was later immortalized in sculpture by Irénée’s brother-in-law who used his actual horns to achieve true likeness. You can go see this homage at Hagley today. And you can see real sheep at Winterthur as part of a collaboration with Greenbank Mills. Back to Winterthur. When Irénée dies suddenly in 1834, parcels of his land, including the original "Merino Farm" (now Martin Farm), are purchased by his son-in-law, James Antoine Bidermann (Antoine). It is on this 450 acres that Antoine and his wife Evelina build a modest home along Clenny run, calling it Winterthur after the Bidermann's home town in Switzerland. This modest home would in time become transformed into the cultural icon as we know it today.

|

AuthorLauren, lover of objects. Archives

February 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed